Blog 10-07-25

1 Umami Rerun

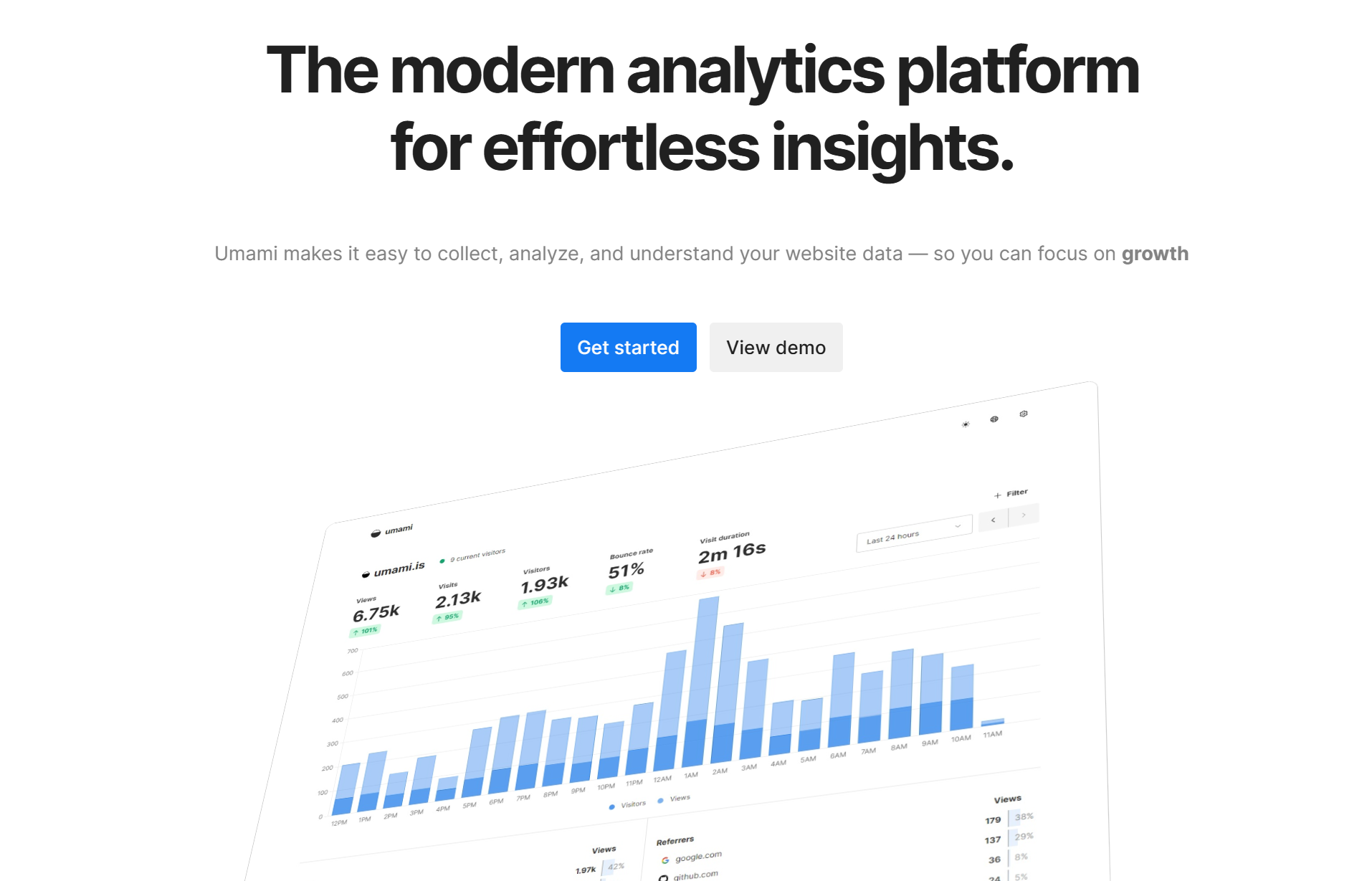

It was time. My trusty old VPS, which had been faithfully collecting website analytics via the fantastic open-source tool Umami, was starting to show its age. Rather than patching it up, I decided to migrate everything to a fresh, new Ubuntu 24.04 server.

Spoiler alert: it was mostly smooth sailing, but I did get haunted by one particularly stubborn PostgreSQL error. If you’re planning a similar move, follow along, and I’ll show you how I solved it.

1.1 The Game Plan: A Two-Pronged Guide

My mission was simple: get the latest Umami (v2.19) running on a new VPS with the newest PostgreSQL (v18). The official Umami documentation is a great starting point, but for the specific nuances of my setup, I knew I needed more.

I decided to use a combination of guides:

- My own previous post on setting up Umami for the core Umami-specific steps.

- A fantastic guide for PostgreSQL 18 on Ubuntu 24.04, as the default repos don’t have it yet.

Let’s break it down.

1.2 Step 1: Laying the Foundation with PostgreSQL 18

Ubuntu 24.04 is a fantastic base, but its default repositories ship with an older PostgreSQL. To get the latest performance and security improvements of version 18, I followed this excellent guide from dev.to: PostgreSQL 17 Installation on Ubuntu 24.04.

Don’t be fooled by the title! The process is identical for version 18. The key steps are:

- Add the Official Repository: This gives us access to the latest versions.

sudo sh -c 'echo "deb https://apt.postgresql.org/pub/repos/apt $(lsb_release -cs)-pgdg main" > /etc/apt/sources.list.d/pgdg.list' - Import the Repository Signing Key:

wget -qO- https://www.postgresql.org/media/keys/ACCC4CF8.asc | sudo tee /etc/apt/trusted.gpg.d/pgdg.asc &>/dev/null - Update and Install:

sudo apt update sudo apt install postgresql-18

Once installed, the service runs automatically. You can create a dedicated database and user for Umami by switching to the postgres user and using the psql command-line tool.

1.3 Step 2: Deploying Umami 2.19

With the database ready, it was time to install Umami itself. I largely followed the process from :(far fa-bookmark): my old blog post, which involves:

- Installing Node.js and npm.

- Cloning the Umami GitHub repository.

- Installing the dependencies with

npm install. - Configuring the

.envfile with the new database connection string. - Building the application and running the database seed script.

Everything went perfectly. The build was successful, the database schema was populated, and I could access the Umami login page.

1.4 The error: “Permission Denied for Schema Public”

Confident that everything was working, I decided to deploy my tracking script to a test site hosted on Vercel. The moment of truth… and it failed.

The Vercel function was throwing a nasty error: permission denied for schema public.

My local setup worked, but the remote connection from Vercel couldn’t insert any data. The issue was one of permissions. In PostgreSQL, when a new user is created, they don’t automatically get USAGE and CREATE privileges on the public schema, even for their own database!

1.5 Solution: Granting the Right Permissions

The solution was found in a lifesaving Stack Overflow answer. It’s a simple one-liner, but it makes all the difference.

Here’s how to fix it:

-

Log into your

psqlprompt as thepostgresuser or a superuser. -

Connect to the Umami database:

\c your_umami_database_name; -

Run this crucial command for your Umami user (in my case,

umami):GRANT ALL ON SCHEMA public TO umami;

That’s it! This single command grants the necessary permissions for the umami user to create tables, functions, and, most importantly, to insert new event data into the existing tables within the public schema.

The moment I ran this and refreshed my test site, the analytics data started flowing in. The ghost was banished.

1.6 Lessons Learned

This migration was a great reminder of a few key things:

- The official docs are your friend, but sometimes you need a more specific map. Combining guides is often the best approach.

- PostgreSQL permissions are strict, and for good reason. A fresh install often requires this extra permission step, which is easy to overlook if you’re used to more permissive defaults.

- Umami continues to be an absolute champion. It’s lightweight, privacy-focused, and a breeze to self-host once you get past these small infrastructure hurdles.

2 Music

I discovered this talented piano guy Riyandi Kusuma:

3 Solving Hugo Image Shortcode Issues: Why Your Images Show Broken Links

If you’ve ever created custom shortcodes in Hugo and encountered mysterious broken image icons, you’re not alone. Today we’re diving into a common issue with image shortcodes and exploring why one approach works while another fails.

3.1 The Problem: Two Similar Codes, Different Results

Recently, I encountered an issue where two seemingly similar Hugo shortcodes behaved completely differently. The first one displayed images perfectly, while the second showed broken link icons. Let’s examine both approaches and understand what went wrong.

3.2 The Working Code

{{- $options := cond .IsNamedParams (.Get "src") (.Get 0) | dict "Src" -}}

{{- $options = cond .IsNamedParams (.Get "alt") (.Get 1) | .Page.RenderString | dict "Alt" | merge $options -}}

{{- $caption := cond .IsNamedParams (.Get "caption") (.Get 2) | .Page.RenderString -}}

{{- $options = dict "Caption" $caption | merge $options -}}

{{- $optim := slice

(dict "Process" "resize 800x webp q75" "descriptor" "800w")

(dict "Process" "resize 1200x webp q75" "descriptor" "1200w")

(dict "Process" "resize 1600x webp q75" "descriptor" "1600w")

-}}

{{- $options = dict "OptimConfig" $optim | merge $options -}}

{{- $options = dict "Loading" "lazy" | merge $options -}}

{{- if .IsNamedParams -}}

{{- $options = dict "Title" (.Get "title") | merge $options -}}

{{- $options = dict "Height" (.Get "height") | merge $options -}}

{{- $options = dict "Width" (.Get "width") | merge $options -}}

{{- $options = .Get "linked" | ne false | dict "Linked" | merge $options -}}

{{- $options = dict "Rel" (.Get "rel") | merge $options -}}

{{- else -}}

{{- $options = cond $caption true false | dict "Linked" | merge $options -}}

{{- end -}}

{{- $options = dict "Resources" .Page.Resources | merge $options -}}

{{- with $caption -}}

<figure{{ with cond $.IsNamedParams ($.Get "class") "" }} class="{{ . }}"{{ end }}>

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" $options -}}

<figcaption class="image-caption">

{{- . | safeHTML -}}

</figcaption>

</figure>

{{- else -}}

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" $options -}}

{{- end -}}3.3 The Broken Code

{{- $options := dict

"Src" (.Get "src")

"Alt" (.Get "alt")

"Caption" (.Get "caption")

"Linked" (.Get "linked" | default true)

"InitialX" (.Get "data-initial-x" | default "50")

"InitialY" (.Get "data-initial-y" | default "50")

"TextboxContents" (.Get "textbox_content")

"SrcSmall" (.Get "src_s")

"SrcLarge" (.Get "src_l")

"Height" (.Get "height")

"Width" (.Get "width")

"Rel" (.Get "rel")

"HoverTooltip" (.Get "hover-tooltip") -}}

{{- $imageSrc := $options.Src | absURL -}}

{{- $small := $options.SrcSmall | default $imageSrc | absURL -}}

{{- $large := $options.SrcLarge | default $imageSrc | absURL -}}

{{- $alt := $options.Alt | default $imageSrc -}}

{{- $options = $options | merge (dict "Resources" .Page.Resources) -}}

{{- if $options.Caption -}}

<figure{{ with cond $.IsNamedParams ($.Get "class") "" }} class="{{ . }}"{{ end }}>

<div class="image-container">

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" (dict "Src" $imageSrc "Alt" $alt "Caption" $options.Caption "Linked" $options.Linked "SrcSmall" $small "SrcLarge" $large "Height" $options.Height "Width" $options.Width "Rel" $options.Rel "Loading" "lazy") -}}

</div>

<figcaption class="image-caption">

{{- $options.Caption | safeHTML -}}

</figcaption>

</figure>

{{- else -}}

<div class="image-container">

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" (dict "Src" $imageSrc "Alt" $alt "Linked" $options.Linked "SrcSmall" $small "SrcLarge" $large "Height" $options.Height "Width" $options.Width "Rel" $options.Rel "Loading" "lazy") -}}

</div>

{{- end -}}3.4 The Root Cause: Understanding Hugo’s Image Processing

The critical difference lies in how each code handles image paths. The broken code uses:

{{- $imageSrc := $options.Src | absURL -}}This seems logical at first glance - we’re converting relative paths to absolute URLs. However, this approach bypasses Hugo’s powerful image processing pipeline.

3.5 Why absURL Breaks Local Image Processing

- Bypasses Resource Pipeline: When you use

absURL, Hugo treats the image as an external URL rather than a local resource that needs processing - No Optimization: The image processing configurations (WebP conversion, resizing, etc.) in your

plugin/image.htmlpartial can’t be applied - Missing Resource Context: The connection to

.Page.Resourcesis lost, so Hugo can’t find and process the local image file

3.6 The Solution: Working With Hugo’s Resource System

Here’s the corrected version that maintains compatibility with Hugo’s image processing:

3.6.1 Solution 1: Pass Raw Paths with Resources

{{- $options := dict

"Src" (.Get "src")

"Alt" (.Get "alt")

"Caption" (.Get "caption")

"Linked" (.Get "linked" | default true)

"InitialX" (.Get "data-initial-x" | default "50")

"InitialY" (.Get "data-initial-y" | default "50")

"TextboxContents" (.Get "textbox_content")

"SrcSmall" (.Get "src_s")

"SrcLarge" (.Get "src_l")

"Height" (.Get "height")

"Width" (.Get "width")

"Rel" (.Get "rel")

"HoverTooltip" (.Get "hover-tooltip")

"Resources" .Page.Resources -}}

{{- if $options.Caption -}}

<figure{{ with cond $.IsNamedParams ($.Get "class") "" }} class="{{ . }}"{{ end }}>

<div class="image-container">

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" $options -}}

</div>

<figcaption class="image-caption">

{{- $options.Caption | safeHTML -}}

</figcaption>

</figure>

{{- else -}}

<div class="image-container">

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" $options -}}

</div>

{{- end -}}3.6.2 Solution 2: Individual Parameters Approach

If your partial expects individual parameters rather than an options dict:

{{- $src := .Get "src" -}}

{{- $alt := .Get "alt" -}}

{{- $caption := .Get "caption" -}}

{{- $srcSmall := .Get "src_s" -}}

{{- $srcLarge := .Get "src_l" -}}

{{- if $caption -}}

<figure{{ with cond $.IsNamedParams ($.Get "class") "" }} class="{{ . }}"{{ end }}>

<div class="image-container">

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" (dict

"Src" $src

"Alt" $alt

"Caption" $caption

"Linked" (.Get "linked" | default true)

"SrcSmall" $srcSmall

"SrcLarge" $srcLarge

"Height" (.Get "height")

"Width" (.Get "width")

"Rel" (.Get "rel")

"Loading" "lazy"

"Resources" .Page.Resources) -}}

</div>

<figcaption class="image-caption">

{{- $caption | safeHTML -}}

</figcaption>

</figure>

{{- else -}}

<div class="image-container">

{{- partial "plugin/image.html" (dict

"Src" $src

"Alt" $alt

"Linked" (.Get "linked" | default true)

"SrcSmall" $srcSmall

"SrcLarge" $srcLarge

"Height" (.Get "height")

"Width" (.Get "width")

"Rel" (.Get "rel")

"Loading" "lazy"

"Resources" .Page.Resources) -}}

</div>

{{- end -}}3.7 Key Takeaways

- Never use

absURLfor local images that need Hugo processing - Always pass

.Page.Resourcesto your image partials - Let Hugo’s pipeline handle URL generation - it knows how to create proper URLs for processed images

- Keep paths raw until they reach the image processing partial

3.8 When to Use absURL

The absURL function is still useful for:

- External images that don’t need processing

- Static assets that aren’t part of Hugo’s resource pipeline

- CDN URLs that are already absolute

3.9 Conclusion

Understanding Hugo’s resource pipeline is crucial for working with images effectively. By letting Hugo handle the entire image processing workflow - from finding local resources to generating optimized output - you ensure that all the powerful features like responsive images, format conversion, and lazy loading work as intended.

The next time you encounter broken images in your Hugo shortcodes, check if you’re accidentally bypassing the resource pipeline with premature URL conversion!